| |

|

The Collision

by

Marc Arsenault ET2

(USS Hartley 1960-61)

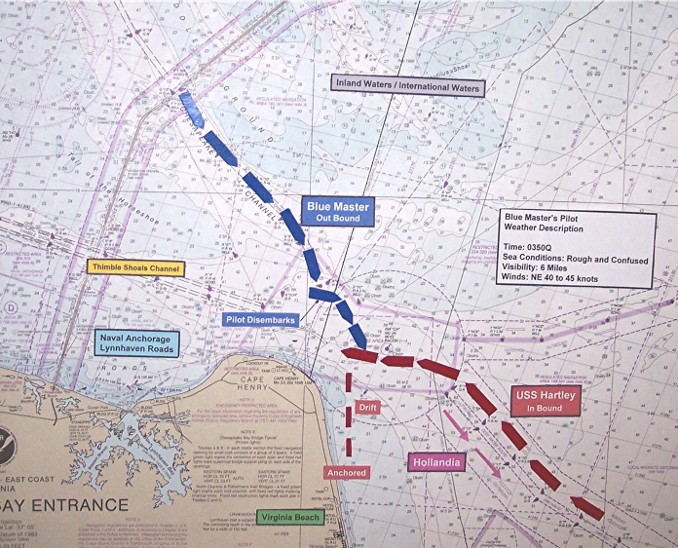

On 16 June, 1965, the USS Hartley DE 1029 in route to the anchorage at Lynn Haven Roads and the

Norwegian Freighter Blue Master in route to New Orleans, collided at the Chesapeake Bay entrance resulting in extensive hull

damage to the Hartley and bow damage to the Blue Master. The official findings of the facts leading up to and following the

collision of the USS Hartley and the Blue Master along with personal interviews were compiled nd summarized in the interest

of simplicity for this Newport Dealeys reunion 2006 presentation.

The following shipmates contributed photos, personal

copies of official files and their verbal recollections of the event.

Reo Beaulieu LCDR Captain of the USS Hartley

John Bonds LT Officer of the Deck

William Litzler LTJG

Bob Funkhouser QM3

John Fry RD2

John

Aluza BT1

Wilbert McCartney MM2

Richard Legg RM1

The circumstances leading up to the collision USS

Hartley At approximately 0800 on the morning of 14 June 1965, the USS Hartley departed Newport RI en-route to Lynn Haven Roads

anchorage via Virginia Capes operating Areas and was scheduled for arrival on 16 June 0600. In addition to her regularly assigned

crew, Hartley embarked a group of Naval Reservists on 13 June for a two week period of active duty for training. Absent on

sailing were the Operation Officer (CIC Officer) one RD2 and one RDSN, who were on temporary Additional duty on board the

USS Long Beach as observers for training exercises. Preparatory to entering the Chesapeake Bay, The Hartley had reveille at

0345 and had scheduled the Special Sea and Anchor Detail for 0400, to relieve the mid watch. Pursuant to direction in his

Night Orders the Commanding Officer LCDR Reo Beaulieu was called at 0345 and was on the bridge at 0348. Upon his arrival the

Captain was briefed by the OOD (LT John Bonds) concerning the navigation situation and the presence of surface contacts.

1. A ship approximately two miles ahead, slightly on the starboard side, showing a green running light.

2.

A pilot vessel slightly to the right of the contact.

3. Farther to the right , another pilot vessel

4. Another

ship farther to the right of the second pilot vessel, showing a green running light approximately four miles.

Blue

Master

The Norwegian Motor Vessel Blue Master departed Baltimore, Maryland, en-route to New Orleans Louisiana

at 1750 on 15 June 1965. During the transit of the Chesapeake Bay at a maintained speed of 16 knots, the Blue Master experienced

weather which was blustery, with rain squalls and increasing northwest winds. Visibility averaged five to ten miles. In the

vicinity of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, The Blue Master slowed to 10 then 5 Knots to avoid overtaking the ship Hollandia

which was also proceeding southward, in order to provide sea room in the vicinity of the pilot vessel for discharge of pilot.

The Blue Master change course left and stopped in order to round up and heave-to to create a lee on the starboard quarter

and to facilitate transfer of the pilot to the pilot vessel by small boat. Visibility was 6 miles. Wind was from the Northeast

at 40-45 knots, seas rough and confused. The Master of the Blue Master was briefed by the Pilot prior to his departure as

to the following contacts:

1. The ship Hollandia, proceeding to sea in an easterly direction.

2. An Alcoa

ship holding station between the CH Buoy and the Thimble Shoals Channel.

3. The Maryland Pilot boat Baltimore and Virginia

pilot boat Relief were cruising east and south oh the CH Buoy. 4. A fisherman (small wooden trawler) was crossing the Blue

Master’s bow inbound.

5. A faint light bearing southeast, distance unknown and was not shown as a contact on the

Blue Masters radar.. At 0350 the Pilot relinquished the conn of the Blue Master to the Captain so he could proceed out to

sea.

|

MV Blue Master (Norway)

|

USS Hartley DE 1029

|

|

|

|

|

The following is a summary of the collision on 16 June 1965, off Little Creek

Virginia between the USS Hartley and the

Norwegian freighter Blue Master as

perceived and communicated by John Bonds to Marc Arsenault on 19 February 2006

LT Bonds was the Officer of the Deck at the time of impact.

Time approximately 4 AM

1. Hartley

was heading towards Norfolk and due to its location was still

operating under International rules. (no horn

signals)

2. Blue Master was heading out to sea and due to its location was operating

under inland

rules.

3. No vessel to vessel communications (before VHF radio)

4. Weather was windy (18-25 mph NE winds)

with fog.

5. Area was cluttered with many small vessels in the area.

6. There were many confusing targets

on the radar. Captain and navigator

were on the bridge, the JOOD had the conn, I was watching the radar,

trying to make sense of the picture. CIC was changing to the sea detail.

7. First visual identification

of the contact which was Blue Master was at

045 relative, about 3500 yards, showing target angle of 060 (range

and

masthead lights plus starboard running light), and stationary. Later

reconstruction revealed

that he had come out of the North Channel

bridge/tunnel opening and was making a lee to debark his bay pilot

in

the area between the north and south channels.

8. Shortly afterward, we noticed a red (port) running

light on the

Blue Master still on our starboard side, and the contact at 2000 yards.

I advised

the CO that the contact had turned to his starboard and was closing.

CO Hartley ordered speed increased to

15kts to cross ahead of the contact,

but continued our course into the south channel bridge opening.

9. Blue Master, now accelerating to sea speed, apparently saw Hartley at the

same time and instinctively

turned to starboard.

10. The two vessels converged rapidly. The range decreased to 1200yds, then

to 800yds, then to 400yds, almost as fast as I could move the cursor and

report the range. Hartley turned

to port to parallel the approaching ship,

but at about 400yds, with both ships now heading South (Cape Henry

light

was dead ahead), Blue Master turned to port—probably realizing that she was

standing

into shallow water on her course. The bow turned into Hartley.

CO Hartley order all ahead flank in an attempt

to move the ship out of the

way of the approaching merchantman, and at the last moment when it was

obvious we weren’t going to get across the bow, he ordered right hard

rudder to try and swing the

stern clear.

11. Blue Master’s bow impacted Hartley at the after bulkhead of the engine

room, and directly into Sick Bay which was obliterated. The hard rudder

swing probably kept the ship from

being cut in half by the impact, as

Blue Master was still accelerating to 16kts, and the bow cut to within

30” of the main keel structure of the DE. The angle of the slice into

the hull of the DE was

perhaps 30deg from a perpendicular attack.

The avoidance maneuver almost worked, but the ship was severely

hit, was

bowled over to port sharply (people on the O1 deck were wet to the waist

afterward either

from rolling down to the water, or the water being pushed

up to the deck by the side motion imparted to Hartley

by the much larger

ship. The bow towered over the bridge level, of course. After a minute

or

two the sideways movement stopped and the ships lay together in the

6-8ft seas, grinding away. Blue Master

hailed over, “Do you require

assistance?” Hartley responded, “Yes, please inform the Coast

Guard of

our situation.” At that point, Blue Master backed out and proceeded

to sea.

12. In Hartley, the ship had gone to GQ when the collision alarm had been

sounded at 400yds.

The DC parties were already out, assessing the damage.

On the bridge, the CO and navigator plotted their position

and the drift

of the ship and readied an anchor. When the ship drifted out of the

channel and

into shallower water, the anchor was dropped and the ship

secured to it.

13. Meanwhile, the

flooding boundaries had been established, and shoring

of the adjacent bulkheads was underway by the courageous

DC teams who

worked steadily while watching the bulkhead “pant” with the seas striking it.

The boundaries were shored on both sides, and they held. We kept fires

in one boiler for a while,

to provide fire main pressure with the steam

pumps in the fire room, but then began to run out of feed water

without

a condenser, and fires were allowed to die out. The emergency generator—the

gas

turbine unit under the helo deck aft—was operational, but the power

cables coming forward from it had

been sliced by the Blue Master’s bow.

So the lights were out, and stayed out except for battle lanterns.

Black oil oozed out of the wound all night, fouling the beaches at Cape Henry.

14. Next day dawned

gray, cold and nasty. But Navy tugs appeared at first light

and attempted to pass a tow line. The messengers

were not strong enough to

withstand the surge of the sea between the tug and the ship, and broke

repeatedly when the tow line was put into the water to be pulled (manually)

to the ship. The seas were breaking

around the ship and the tug could not

get close enough, so a brave helo driver delivered a stronger messenger

line,

dragging it across the foc’sle of the DE, where the entire crew was mustered

to pull

in the tow line. It was finally made fast, the anchor chain slipped,

and the tow to Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

began.

Five months of repairs commenced immediately, together with a formal Navy

investigation

of the incident. Both ships were found to be at fault in the

incident, and shared the damages/loss of services

of the ship bill equally,

as I recall.

LT John B. Bonds

|

|

|

|

USS Hartley Anchored off Virginia Beach

|

Finding

of Facts Events transpiring subsequent to the collision 1. Upon with drawing from the Hartley’s side, Blue Master

inflicted additional damage to the Hartley superstructure as ships rolled together.

2. Hartley lost all propulsion and

electrical power as a consequence of the flooding of the only engine space and severing of the wire way supplying power

forward.

3. Preliminary shoring was installed by the repair parties on their own initiative in areas surrounding the

damage.

4. Until about 0454Q, The Commanding Officer permitted the Hartley to drift in a southerly direction in order

to clear the Chesapeake Bay Entrance traffic lanes and to place the Hartley closer to the shore in the event that it became

necessary to abandon ship, finally dropping anchor at Latitude 36-53N, Longitude 75-58W

5. Commencing about 0620Q units

of the Coast Guard arrive on the scene and proceeded to take Hartley under tow, succeeding finally at 1438Q when the Hartley

slipped anchor and the Kiowa, with the Senec on her starboard quarter, got under way in tow. They proceed up the Thimble Channel

to the Destroyer- Submarine Pier 2 arriving at 2340Q

6. On June 18 1965, the Hartley was towed from the D&S piers

to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard for repairs having first off loaded ammunition.

7. As a result of the collision, the USS

Hartley sustained hull and equipment damage estimated in a preliminary survey by the U.S. Salvage Association at $700,000

(1965 $). This estimate did not include the expense of towing the Hartley into port, nor the cost of subsequent salvage

of Hartley’s anchor.

|

|

Finding of Facts

Opinions

1. The collision occurred in International Waters.

2. The

Hartley at all times was in International Waters

3. The Hollandia was the contact which Hartley passed port to port

between 0350Qand 0355Q. It is probable that the Hollandia merged

with Hartley as a radar target, thus

precluding early visual or radar

detection by the Blue Master as a separate contact.

4. The Blue Master approached

the point of impact from Inland Waters.

5. The actions of Blue Master in coming to her departure course changed

the presentation of her side light to Hartley from green to red, and had

the effect of an illegal action to

change an unequivocal “clear to

starboard” situation into a crossing situation which burdened Hartley

shortly before development of “in extremis”

6. The Hartley was proceeding upon her legitimate

course to enter Thimble

Shoals Channel.

7. The development of this collision situation was brought about by

the

Blue Masters’s second change of course to the right when the range had

closed to about 1200

yards. This course change by the Blue Master to

the right was illegal.

8. In response to Blue Masters second

change of course to the right,

Hartley’s change of course to the left and effort to increase speed to

20 knots were prudent actions and justified by the developed “in extremis

situation. This action, in

an unchanging situation, should have enabled

Hartley to parallel Blue Master’s course and run out ahead.

9. The subsequent change of course to the left by Blue Master nullified

Hartley’s evasive action.

10. After

sighting Blue Master’s red side light on her own starboard bow,

Hartley’s decision to increase speed

to cross ahead of Blue Master was

an error in judgment by the C.O. of the Hartley, and an illegal movement,

despite a reasonable prior expectation held by Hartley that the Blue Master

intended to pass astern of the

Hartley and proceed southeasterly to

seaward as indicated by her movements up to that time.

11. A series of

short whistle blast sounded by the Blue master construed to

be the danger signal, were heard by the Hartley personnel

immediately

prior to the collision.

12. Hartley’s whistle was operative. Yet, Hartley erred in not sounding

any whistle signals, incident to her maneuvers.

13. The action of the Hartley’s Commanding Officer in

ordering hard

right rudder militated against more extensive damage to both ships,

probably save Hartley

from being severed, and was material factor in

the fact that there was no loss of life, nor occurrence of serious

injury.

14. The actions of the damage control parties were proper and effective in

controlling and in minimizing

the damage resulting from the collision.

15. The overall conduct of Hartley’s crew subsequent to the collision

was

exemplary and in the best traditions of the Naval service.

Finding of Facts

Summary

In summary it must be considered that both ships contributed to the

collision through errors in judgment and must

be held to share the

culpability: Blue Master’s violation of the Rules of Good Seamanship

as well as the

General Prudent Rule in addition to other violations

of the Rules of the Road, make the Blue Master’s culpability

the greater.

|

A first hand account of the

collision of the USS Hartley DE 1029 and

Norwegian Freighter Blue Master

as

told by HTCM T. D.

Lathrop, USN/Ret.

June 1965, Newport, RI, as I walked up the gang way to the

quarter deck of the USS Hartley, sea bag on the shoulder, orders in hand, I was greeted by a First Class Ship Fitter, who

said "Boy am I glad you're here" handed me a ring of keys, he then saluted the Ensign and called back to me "good

luck on this one" and he disappeared down the pier. After I checked in, I was informed we were getting underway by the weekend to go down to Norfolk area and

then head back up for a North Atlantic cruise. It

took a couple of days to get housing arranged, schools for my kids and next thing I knew we were leaving port. I'd been in

the shop area one day, met the fellows that made up R division. I found a bunk and locker in the Engineering 1st

class section, which was a small 8 bunk compartment off the starboard side of the Engineering berthing. The next day, I took

inventory of R division spaces, met more crew and then took in depth tour of the Hartley. Taps, lights out, and sea detail

at 0400 next day. I recall reveille, sea detail being announced over the 1MC, then BANG, got knocked out of my rack, lights

flickering, people yelling, heard "engine room blew up", "hit a mine", everyone scrambling for the only

scuttle out of compartment. When I came through the scuttle onto fantail, I looked forward, could see starboard main deck

peeled up in the air, steam blowing and a huge forward section of a dark ship that appeared to have cut us in half. It was

pushing us sideways, we were leaning over to the port and I remember looking up what seemed like 80 - 90 feet to their foc'sle

area and seeing one small flashlight peering down on us. The seas were rough, wind blowing, spitting rain, the side push came to a halt, then suddenly the freighter

slowly backed out of the ship. The Hartley came upright then slowly started to list to the starboard side. In all the confusion,

I don't recall the collision alarm or GQ alarm being announced, which conflicts to the report. Damage control is an R Division responsibility. I looked around at unfamiliar

faces, said we need a damage assessment now, the faces jumped up and took off to investigate. One of the ship fitters opened

the DC locker and brought some emergency lanterns. My

new found friend was an engine man 1st class, think his name was Phillyar, a big stout guy.

As the faces came back with their reports, it was apparent

the compartment aft the engine room, forward bulkhead and starboard skin would need to be shored up to prevent flooding and

further damage. Yelling out, we need shoring

timbers, shoring kit, more lights. Phillyar came back, looked like a northwest logger, with shoring and helpers. We went down

into the compartment, it was taking on water. We had to keep a steady stream of lights coming as each one would only last

for a few minutes, then die. We got mattresses stuffed into the big rip, backed up with a bunk bottom and shored it into place.

Then started on the forward bulkhead, it took two guys to hold the floating shore and one to cut by hand, then stand on them

to hold in place so they wouldn't float back up. Overhead shoring was a little easier, you could see the wedges to hammer

in place. We all came back up on deck,

told Phillyar we need to start pumping out the flooded space. There was a P-500 on the fantail, rigged it up to pump out,

pulled on the starter rope numerous times, finally sputtered to life, then suddenly quit. A quick check revealed that it had

seized up. I told Phillyar, I saw another P-500 forward near foc'sle, bring that back here, we changed everything over

to that pump, went to fire it up, we broke both starting ropes, it was seized up tight!! No pumps. During all that commotion, there was a coast guard helicopter hovering

over our helo pad. Someone yelled that the Captain wants to see me up on Helo deck, I ran up there, he said I don't know your

name, but do we need any assistance? I told him we need pumps to start dewatering. The coast Guard had lowered a pad and a

pencil, I wrote we needed dewatering pumps with suction lines, he retracted the clip board, gave me a thumbs up, flew off,

they returned shortly with two big salvage pumps and all the gear, I thanked them with a big thumbs up.

We got everything hooked up and finally started to make headway

on dewatering. I do remember the tug trying

to get a tow line aboard. The messenger line would break because of rough seas. On their last effort, you could see the tugs

screw kick up sand off the bottom, it was almost time to abandon ship to get ashore, but the helo took the line from the tug

and slowly inched his way across the foc'sle and the crew up there was able to hold on, then it was all hands to pull the

tow howser on board. Follow-on Comments LT John Bond

USS Hartley I

would like to stress again the calm professional courage exhibited by the Damage Control personal, who were standing in knee-deep

water with a steel bulkhead flexing about 4 inches in front of them, and a 14 inch scuttle the only way out of the compartment.

They all knew if that bulkhead let go before they could shore it, only one person would get out of the compartment. They worked

fast, skillfully and with humor. The guy sawing the shoring timber to fit was whistling while he worked. The Navy at its best,

doing his job, in the face of quite real danger.

CO USS Hartley I would like to make one comment. In both the findings of fact and the opinions,

it was noted that the bearing drift on the Bluemaster was always to the right, going from 318 to 330. This was a major factor

in my decision to increase speed and pass ahead of the vessel. If Bluemaster had maintained course at that time, we would

have certainly passed ahead of her. However, as hindsight would have it, I guess Bluemaster's intent was always to effect

a port to port passage. Too bad I didn't realize it at the time. I believe you have done a great job in your presentation.

Please let me know how it was received at the reunion and the reactions of others that were involved. Sincerely

Reo Beaulieu

|

|

|

Richard Legg RM1 Checking out the damage

|

Flight Deck looking aft

|

|

Ltjg Thasher, Comm Officer, was thrown

from his bunk to deck,

stumbled out of after "O" and stared at Blue Master's markings.

Then climbed up the twisted ladder,

through the hatch to the main deck.

Ended up on the bridge in his skivies.

|

Drydock

Portsmouth

Naval Shipyard

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wilbert McCartney MM2 was at

his station in the engine room

when the Blue Master's bow came within 4 ft of him.

Note the day light opening

above to the dry dock. (Red lines) |

|

|

|